Your typical Victorian basic bitches

The face of an inveterate liar

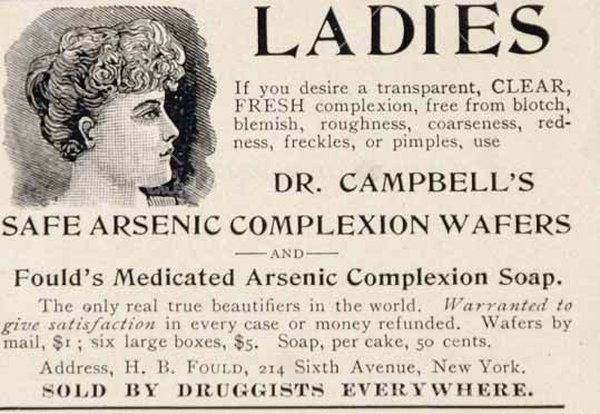

Murder your husband and rejuvenate your skin all with one handy substance!

Peak aesthetic

Circe, goddess of pharmakeia, which can refer to both sorcery and medicine. Natural scientist or vicious slattern? You decide.

Victorian Jezebel: Virginie Gautreau.

Victorian Cosmetics: The Ugly Girl Papers

Your typical Victorian basic bitches

Why, hello there! Forgive my bad manners, I didn't see you lurking there. Why...why are you slowly backing away from me? Is there something on my face?

As it turns out, there were plenty of things on a Victorian lady's face, and not all of them pleasant. Welcome to Everything's Awful Forever: Text Edition™! If you listened to our very first episode on Victorian Cosmetics (now available only on YouTube) and wanted to know even more about the (almost literal) shit that the Victorians used to make themselves pretty, then come on in to our boudoir of terrors.

(Incidentally, did you know that the word boudoir comes from the French bouder, which means to pout or to sulk? Possibly because Victorian husbands were tired of being sent to sleep on the sofa after telling their wives that they preferred women who didn't wear make-up.)

As it turns out, there were plenty of things on a Victorian lady's face, and not all of them pleasant. Welcome to Everything's Awful Forever: Text Edition™! If you listened to our very first episode on Victorian Cosmetics (now available only on YouTube) and wanted to know even more about the (almost literal) shit that the Victorians used to make themselves pretty, then come on in to our boudoir of terrors.

(Incidentally, did you know that the word boudoir comes from the French bouder, which means to pout or to sulk? Possibly because Victorian husbands were tired of being sent to sleep on the sofa after telling their wives that they preferred women who didn't wear make-up.)

The face of an inveterate liar

Painted Women

Of course, before we dive into the poisonous world of Victorian make-up, we first need to know...should we?

The 21st century has become considerably more forgiving towards make-up, and beauty tutorials can be found in their hundreds on the internet. Yeah, mothers still tell their daughters that Arson Red is probably not the shade for them (don't want to betray the glorious revolution at such a young age, ladies) and boyfriends-in-waiting feel the need to tell women that they prefer a "natural" look, but the artistry and creative potential to be found in make-up is increasingly recognised.

These two opposing trends, the natural and the unnatural, butted heads in the Victorian Era as well, with the natural being the more popular in the wealthier classes. Everyone knows that inner beauty and outer beauty go hand in hand. Therefore, only sullied, morally-tainted harlots needed to stain their cheeks with rouge. Quod est demonstrandum, my dear. And so, women who knew better needed to get crafty with their make-up when cultivating the "natural" look. This mostly meant focusing on one's complexion.

Of course, in the 1800s, there werewomen painted jezebels who didn't bother to keep their make-up game subtle. But for the most part, obvious make-up indicated poor quality make-up, which suggested that you were significantly lacking in natural beauty, class, and summer houses out in the countryside.

(And perhaps this feeds back into the idea of women with their potions and tonics, deceivors and witches the lot of 'em, fooling men with their paints, glamours, and false advertising on Instagram. Can't trust any of them!)

If you didn't want anyone to find out about your shameful need to cover your hideousness with product, you might want to consider concealing your concealer. Women would frequently buy bottles of medicine at their local apothecary, empty it out, and then fill it with their poisonous concoctions.

Alternatively, the evidence of their iniquity would be stuffed under floorboards or in medicine chests.

The 21st century has become considerably more forgiving towards make-up, and beauty tutorials can be found in their hundreds on the internet. Yeah, mothers still tell their daughters that Arson Red is probably not the shade for them (don't want to betray the glorious revolution at such a young age, ladies) and boyfriends-in-waiting feel the need to tell women that they prefer a "natural" look, but the artistry and creative potential to be found in make-up is increasingly recognised.

These two opposing trends, the natural and the unnatural, butted heads in the Victorian Era as well, with the natural being the more popular in the wealthier classes. Everyone knows that inner beauty and outer beauty go hand in hand. Therefore, only sullied, morally-tainted harlots needed to stain their cheeks with rouge. Quod est demonstrandum, my dear. And so, women who knew better needed to get crafty with their make-up when cultivating the "natural" look. This mostly meant focusing on one's complexion.

Of course, in the 1800s, there were

(And perhaps this feeds back into the idea of women with their potions and tonics, deceivors and witches the lot of 'em, fooling men with their paints, glamours, and false advertising on Instagram. Can't trust any of them!)

If you didn't want anyone to find out about your shameful need to cover your hideousness with product, you might want to consider concealing your concealer. Women would frequently buy bottles of medicine at their local apothecary, empty it out, and then fill it with their poisonous concoctions.

Alternatively, the evidence of their iniquity would be stuffed under floorboards or in medicine chests.

Dealing with Odour

Before you start dealing with your monstrous appearance, you might want to make sure that your ungodly stench isn't scaring anyone away. This, at least, was seen as acceptable behaviour in women and men alike, and the necessary products could be easily acquired.

Ballrooms are hot and stuffy at the best and most fragrant of times. Armpit sweat and bad breath might exponentially increase the need for smelling salts.

To combat the charnel-house fumes wafting from your gaping maw, charcoal biscuits were an effective way to clean your teeth. A chlorine-based mouth wash didn't hurt, either.

But perhaps you're smelly and poor. Don't worry, there are budget-friendly alternatives. 'The Ugly Girl Papers - Hints for the Toilet', an advice column from Harper's Bazaar, suggest scraping the charcoal from your burnt toast. As this text also recommends a mouthwash made with brandy, spirits of camphor (poisonous), and myrrh for rotting teeth, we suggest sticking to charcoal.

(These toast-scrapings could also be applied to your lashes if you craved a smokey-eye look, but eyeliner and mascara were only for the very brave.)

As for the sweaty tang of your clothing, multiple applications of perfume should hopefully do the trick. The Victorians were a little more pro-bathing than their Georgian forbears, but body odour was still a pungent fact of life for many.

By the Victorian period, the fashion for overpowering scents had subsided, and orange blossom eau de cologne was popular, and more accessible to the masses than "true" perfume, which contained only essential oils, rather than being diluted with distilled water.

Lemon and bergamot scents were also commonly used up until the end of the century, when the heavier scents of musk, ambergris, and patchouli were becoming increasingly fashionable again, especially among the rich, who were the only ones able to afford these complex fragrances.

Again, there were home remedies for the financially deficient. Ladies on a budget could use natural ingredients to concoct their own scents: lavender, cinnamon, and herbs would cover for an expensive bottle of scent in a pinch.

Ballrooms are hot and stuffy at the best and most fragrant of times. Armpit sweat and bad breath might exponentially increase the need for smelling salts.

To combat the charnel-house fumes wafting from your gaping maw, charcoal biscuits were an effective way to clean your teeth. A chlorine-based mouth wash didn't hurt, either.

But perhaps you're smelly and poor. Don't worry, there are budget-friendly alternatives. 'The Ugly Girl Papers - Hints for the Toilet', an advice column from Harper's Bazaar, suggest scraping the charcoal from your burnt toast. As this text also recommends a mouthwash made with brandy, spirits of camphor (poisonous), and myrrh for rotting teeth, we suggest sticking to charcoal.

(These toast-scrapings could also be applied to your lashes if you craved a smokey-eye look, but eyeliner and mascara were only for the very brave.)

As for the sweaty tang of your clothing, multiple applications of perfume should hopefully do the trick. The Victorians were a little more pro-bathing than their Georgian forbears, but body odour was still a pungent fact of life for many.

By the Victorian period, the fashion for overpowering scents had subsided, and orange blossom eau de cologne was popular, and more accessible to the masses than "true" perfume, which contained only essential oils, rather than being diluted with distilled water.

Lemon and bergamot scents were also commonly used up until the end of the century, when the heavier scents of musk, ambergris, and patchouli were becoming increasingly fashionable again, especially among the rich, who were the only ones able to afford these complex fragrances.

Again, there were home remedies for the financially deficient. Ladies on a budget could use natural ingredients to concoct their own scents: lavender, cinnamon, and herbs would cover for an expensive bottle of scent in a pinch.

Murder your husband and rejuvenate your skin all with one handy substance!

Skincare

Cleanliness is next to godliness, but a pale complexion was a sign of class. You don't want people thinking that you toil in the sun like some peasant girl, after all. An almost translucent pallour was the most desirable look of all, and beauty tips abounded.

Lola Montez, the original Gwyneth Paltrow, advertised damaging beauty methods in her book The Arts of Beauty, Or, Secrets of A Lady's Toilet. In her book, she expounds the values of a nice, cosy arsenic bath. She does mention that these baths are dangerous, but just look at the gorgeous effect that it has on the complexion!

'The Ugly Girl Papers' suggested applying lettuce leaves to the face, taking advantage of the slight traces of opium to be found in them. Also: washing your face with ammonia (see above chapter on combatting odour).

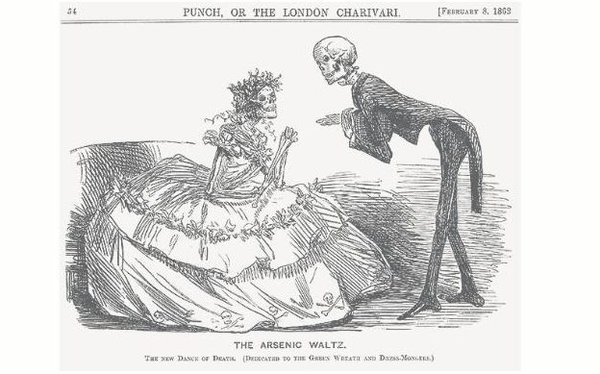

You could also use arsenic to burn away your freckles, because nothing screams "country bumpkin" like a little melatonin. What's a little damage to the nervous system or kidneys in the name of beauty? Arsenic is also an addictive substance that, in small doses, gives a feeling of mild euphoria (men used it as a form of viagra), so the situation is win-win, really. (For a more extensive discussion of the hundred of ways that Victorians enjoyed poisoning themselves, see The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play by James Whorton.)

Safer alternatives came into existence, and zinc oxide, a white mineral powder, became a popular method of achieving a pale complexion, although women continued to use lead, ammonia, and arsenic well into the 1800s.

Lola Montez, the original Gwyneth Paltrow, advertised damaging beauty methods in her book The Arts of Beauty, Or, Secrets of A Lady's Toilet. In her book, she expounds the values of a nice, cosy arsenic bath. She does mention that these baths are dangerous, but just look at the gorgeous effect that it has on the complexion!

'The Ugly Girl Papers' suggested applying lettuce leaves to the face, taking advantage of the slight traces of opium to be found in them. Also: washing your face with ammonia (see above chapter on combatting odour).

You could also use arsenic to burn away your freckles, because nothing screams "country bumpkin" like a little melatonin. What's a little damage to the nervous system or kidneys in the name of beauty? Arsenic is also an addictive substance that, in small doses, gives a feeling of mild euphoria (men used it as a form of viagra), so the situation is win-win, really. (For a more extensive discussion of the hundred of ways that Victorians enjoyed poisoning themselves, see The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play by James Whorton.)

Safer alternatives came into existence, and zinc oxide, a white mineral powder, became a popular method of achieving a pale complexion, although women continued to use lead, ammonia, and arsenic well into the 1800s.

Cosmetics

What if you wanted to throw common sense to the wind and go for a more risqué make-up routine? Dare we say...a bit of colour?

Women used a variety of ingredients to add a soft blush to their cheeks and lips, but these were applied with great care to avoid it being too obvious. One misstep and you ended up looking like Great-Aunt Mildred, blind and unmarried, who applied her make-up with all the subtlety of a Parisian brothel-worker.

For the cheeks, Victorian women might use beet juice or animal blood, while vermillion, also known as red mercury, was used to tint the lips and was known to be poisonous.

"Painted women" would also counter-intuitively paint themselves white with lead, to give the impression of a pale complexion. Being corrosive in nature, lead would inflict damage on the skin, leading to a vicious cycle: the more you applied in the present, the more you would need in the future.

Lead also cracks easily, and so women who employed it would have to be careful to keep their faces expressionless.

Lead paint, or enamelling, was controversial and lacking in subtlety, and not every Victorian woman would have employed it as part of her toilet. Victorian society was not hesitant to mock those whose beauty was ruined through the application of this deadly mineral substance, and Montez, in the The Arts of Beauty confidently states:

“If Satan has ever had any direct agency in inducing woman to spoil or deform her own beauty, it must have been in tempting her to use paints and enameling.”

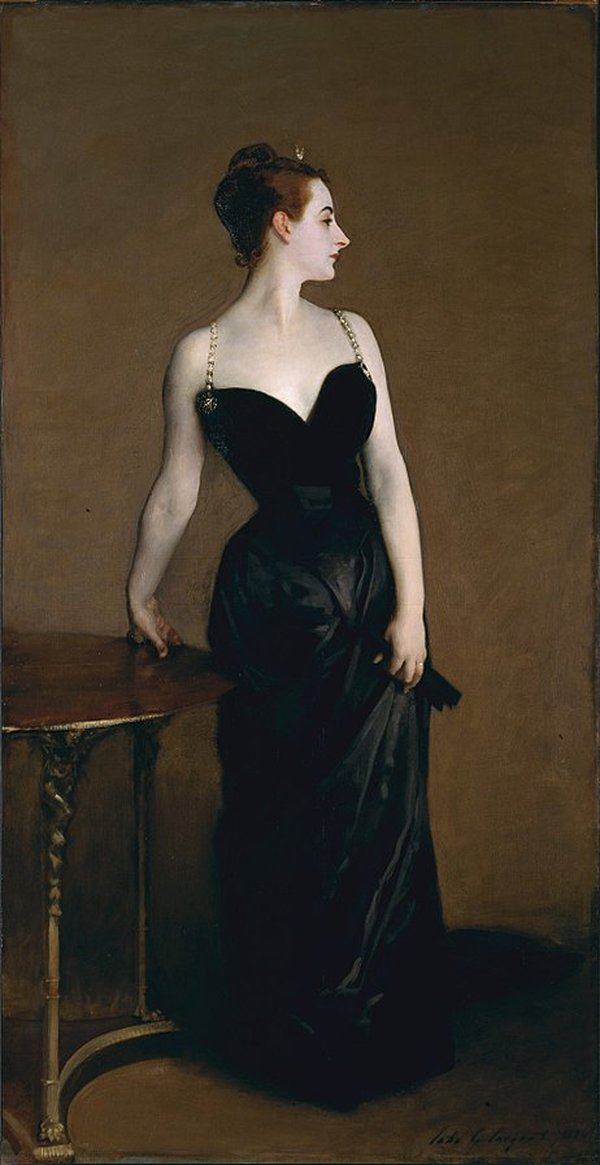

Of course, other women deliberately invited infamy and scandal by flaunting their skill with lead cosmetics. Virginie Gautreau, the subject of Sargent's Madame X, took the aesthetic even further by painting blue veins onto her dyed skin, and applied a lavender face powder to cultivate a deathly glow.

Women used a variety of ingredients to add a soft blush to their cheeks and lips, but these were applied with great care to avoid it being too obvious. One misstep and you ended up looking like Great-Aunt Mildred, blind and unmarried, who applied her make-up with all the subtlety of a Parisian brothel-worker.

For the cheeks, Victorian women might use beet juice or animal blood, while vermillion, also known as red mercury, was used to tint the lips and was known to be poisonous.

"Painted women" would also counter-intuitively paint themselves white with lead, to give the impression of a pale complexion. Being corrosive in nature, lead would inflict damage on the skin, leading to a vicious cycle: the more you applied in the present, the more you would need in the future.

Lead also cracks easily, and so women who employed it would have to be careful to keep their faces expressionless.

Lead paint, or enamelling, was controversial and lacking in subtlety, and not every Victorian woman would have employed it as part of her toilet. Victorian society was not hesitant to mock those whose beauty was ruined through the application of this deadly mineral substance, and Montez, in the The Arts of Beauty confidently states:

“If Satan has ever had any direct agency in inducing woman to spoil or deform her own beauty, it must have been in tempting her to use paints and enameling.”

Of course, other women deliberately invited infamy and scandal by flaunting their skill with lead cosmetics. Virginie Gautreau, the subject of Sargent's Madame X, took the aesthetic even further by painting blue veins onto her dyed skin, and applied a lavender face powder to cultivate a deathly glow.

Peak aesthetic

Healthy Glow

“The death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” - Edgar Allan Poe

The prevailing aesthetic for a desirable Victorian maiden was "about to die". Some had it lucky and contracted tuberculosis (for a fascinating discussion of this trend, see Carolyn Day's Consumptive Chic: A History of Fashion, Beauty, and Disease or listen to our 59th episode: Consuming Fashion). After all, the disease naturally mimicked the signs of beauty and desire, such as dilated pupils, flushed cheeks, and watery, shining eyes. Also, it was just so terribly romantic: a young, nubile woman ripe for marriage but fated to die.

The less fortunate had to take matters into their own hands. If your constitution was too hardy to cultivate a natural sickly, delicate pallour, fitting of a true Victorian heroine, you might consider applying drops of deadly nightshade to your eyes. An alternative name for this plant, belladonna, literally translates to beautiful woman and its symptoms include eventual blindless and tripping balls. Try reading Pride and Prejudice with the understanding that the more "superficial" female characters were probably hallucinating Satan.

(Women could also use drops of lemon juice in their eyes, but we'll opt for the poisonous hallucinogenic, please.)

As tubercolosis also led to weight loss, a thin, fragile body was necessary for the cultivation of true Victorian beauty. Unsurprisingly, corsets, starvation, and tapeworm diets were the prescribed methods of achieving this.

(But how to remove the tapeworm, you might ask, once you have achieved your goal weight. One suggestion was to sit in front of a bowl of milk: the tapeworm would be drawn to this calcium-rich beverage and slither out of you. Alternatively, you could try a device created by one Dr. Meyers: a metal cylinder filled with food that would be inserted down the throat of thevictim patient. The patient would then abstain from food for several days, forcing the tapeworm into the cylinder, which would then be removed. Did either of these methods work? If you need to ask, then I do not recommend either of these weightloss strategies.)

Doctors and the public in general became increasingly aware of the effects that corsets had on the body and the damage that it inflicted on the wearer's muscles and organs, but women just kept on insisting on wearing the damn things! It was almost like they believed their beauty to be intrinsically linked to their worth as a person, the poor, addled darlings.

This is true of a number of these poisonous beauty remedies. Women knew that arsenic was deadly. After all, they used it to poison their husbands. The continued use of these products may be because of the well-known Victorian obsession with death and the fact that looming mortality was a day-to-day fact in the lives of all Victorians.

But in the absence of better, safer alternatives, what was a girl to do? Die in the name of a pretty face, apparently.

The prevailing aesthetic for a desirable Victorian maiden was "about to die". Some had it lucky and contracted tuberculosis (for a fascinating discussion of this trend, see Carolyn Day's Consumptive Chic: A History of Fashion, Beauty, and Disease or listen to our 59th episode: Consuming Fashion). After all, the disease naturally mimicked the signs of beauty and desire, such as dilated pupils, flushed cheeks, and watery, shining eyes. Also, it was just so terribly romantic: a young, nubile woman ripe for marriage but fated to die.

The less fortunate had to take matters into their own hands. If your constitution was too hardy to cultivate a natural sickly, delicate pallour, fitting of a true Victorian heroine, you might consider applying drops of deadly nightshade to your eyes. An alternative name for this plant, belladonna, literally translates to beautiful woman and its symptoms include eventual blindless and tripping balls. Try reading Pride and Prejudice with the understanding that the more "superficial" female characters were probably hallucinating Satan.

(Women could also use drops of lemon juice in their eyes, but we'll opt for the poisonous hallucinogenic, please.)

As tubercolosis also led to weight loss, a thin, fragile body was necessary for the cultivation of true Victorian beauty. Unsurprisingly, corsets, starvation, and tapeworm diets were the prescribed methods of achieving this.

(But how to remove the tapeworm, you might ask, once you have achieved your goal weight. One suggestion was to sit in front of a bowl of milk: the tapeworm would be drawn to this calcium-rich beverage and slither out of you. Alternatively, you could try a device created by one Dr. Meyers: a metal cylinder filled with food that would be inserted down the throat of the

Doctors and the public in general became increasingly aware of the effects that corsets had on the body and the damage that it inflicted on the wearer's muscles and organs, but women just kept on insisting on wearing the damn things! It was almost like they believed their beauty to be intrinsically linked to their worth as a person, the poor, addled darlings.

This is true of a number of these poisonous beauty remedies. Women knew that arsenic was deadly. After all, they used it to poison their husbands. The continued use of these products may be because of the well-known Victorian obsession with death and the fact that looming mortality was a day-to-day fact in the lives of all Victorians.

But in the absence of better, safer alternatives, what was a girl to do? Die in the name of a pretty face, apparently.

Circe, goddess of pharmakeia, which can refer to both sorcery and medicine. Natural scientist or vicious slattern? You decide.

Any Last Words?

Men were not unaware of the crimes against nature that women were committing with paint and powder. They certainly weren't shy in expression their opinions on the matter.

Quoth Dr James P. Tuttle, in the 25th volume of The Medical Record: "The science of chemistry and art of pharmacy have been exhausted to prepare delicate colorings and bright enamels for the complexion. It seems to have been a conception of the ages past that these adornments added to the personal attractions of men as well as women, inflaming passion and calling forth amorous ebullitions in the opposite sex. That it should be held in disrepute will not be questioned, for it was those whose consciences did not falter at whatever means to gain an end - the vicious and vulgar, the harlots and witches - who were the originators of these practices."

Quoth Dr James P. Tuttle, in the 25th volume of The Medical Record: "The science of chemistry and art of pharmacy have been exhausted to prepare delicate colorings and bright enamels for the complexion. It seems to have been a conception of the ages past that these adornments added to the personal attractions of men as well as women, inflaming passion and calling forth amorous ebullitions in the opposite sex. That it should be held in disrepute will not be questioned, for it was those whose consciences did not falter at whatever means to gain an end - the vicious and vulgar, the harlots and witches - who were the originators of these practices."

Victorian Jezebel: Virginie Gautreau.

If you enjoyed this, consider fuelling the writer's sleepless nights with a cup of coffee. We're truly grateful for any support!

Resources

Original Sources:

Montez, L. (1858) The Arts of Beauty: Or, Secrets of a Lady's Toilet New York: Dick & Fitzgerald

Power, S. (1874) The Ugly-Girl Papers: Or, Hints for the Toilet New York: Harper & Brothers

Books:

Goodman, R. (2017) How to be a Victorian: A Dawn-To-Dusk Guide to Victorian Life New York, London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, Reprint Edition

Internet texts:

Beautiful with Brains: 'Beauty in the Victorian Age' (2010)

Atlas Obscura: The Poisonous Beauty Advice Columns of Victorian England (2015)

Artwork:

Sargent, J. (1884) Portrait of Madame X [Oil on canvas]. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Manhattan

Waterhouse, J. (1892) Circe Invidiosa [Oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Montez, L. (1858) The Arts of Beauty: Or, Secrets of a Lady's Toilet New York: Dick & Fitzgerald

Power, S. (1874) The Ugly-Girl Papers: Or, Hints for the Toilet New York: Harper & Brothers

Books:

Goodman, R. (2017) How to be a Victorian: A Dawn-To-Dusk Guide to Victorian Life New York, London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, Reprint Edition

Internet texts:

Beautiful with Brains: 'Beauty in the Victorian Age' (2010)

Atlas Obscura: The Poisonous Beauty Advice Columns of Victorian England (2015)

Artwork:

Sargent, J. (1884) Portrait of Madame X [Oil on canvas]. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Manhattan

Waterhouse, J. (1892) Circe Invidiosa [Oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide